In one of my favorite moments of Toy Story 3, Mr. Pricklepants, a stuffed (and stuffy) porcupine asks Woody in a smug tone, “are you classically trained?” This lederhosen-wearing porcupine, while cute, has airs of superiority. I find it interesting that Mr. Pricklepants’ question seeks to learn whether Woody is classically trained, albeit of the thespian variety.

Classical Christian educators should keep in mind that it is indeed possible for classical schools and classically-trained minds to grow proud and aloof, taking themselves too seriously (like Woody’s friend, Mr. Picklepants). In order to mitigate the risk, classical Christian educators should heed the example of G.K. Chesterton, a man whose herculean intellect made its impact on the world because of his even greater imagination. Chesterton’s robust mind was coupled with a sense of playfulness and levity. This was, after all, the man who said angels fly because they take themselves lightly.

Before seeing Chesterton’s levity at work, some background is in order. During the 1950s (nearly two decades after Chesterton’s death), Dr. Alfred Kessler stumbled upon a gem. Kessler, a fan of Chesterton, found a used book in a San Francisco bookstore entitled Platitudes in the Making: Precepts and Advices for Gentryfolk by Holbrook Jackson. What made this book special is that it was a copy of the book given to Chesterton by Holbrook Jackson himself. Jackson and Chesterton, while friends, were worlds apart theologically and philosophically so the copy of Jackson’s book found by Kessler was laced with Chesterton’s witty remarks on the platitudes in Chesterton’s own handwriting. Chesterton’s handwritten comments provide a fascinating window into Chesterton’s playfulness and wit at work.

Some of my favorite Chesterton quips include the following:

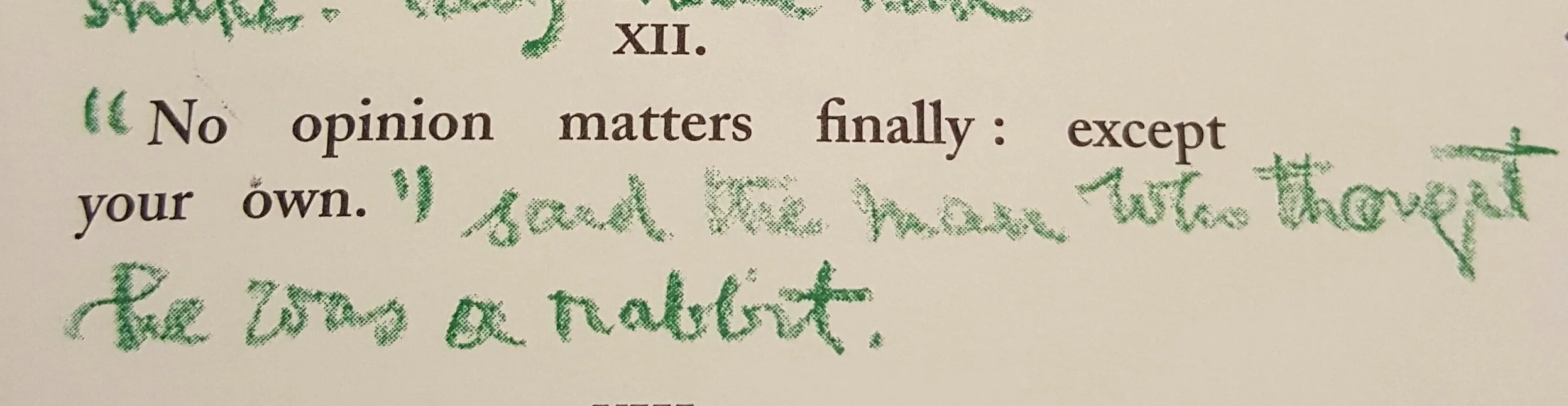

Jackson’s platitude: “No opinion matters finally: except your own.”

Chesterton’s handwritten comment: “…said the man who thought he was a rabbit.”

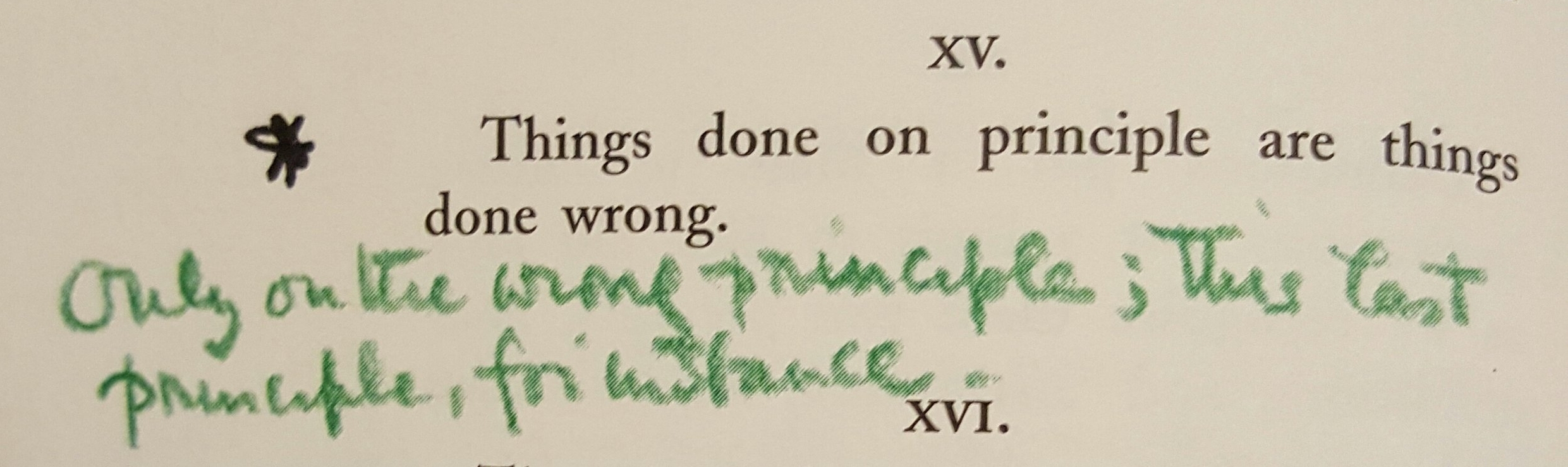

Jackson’s platitude: “Things done on principle are things done wrong.”

Chesterton’s handwritten comment: “Only on the wrong principle. This last principle, for instance.”

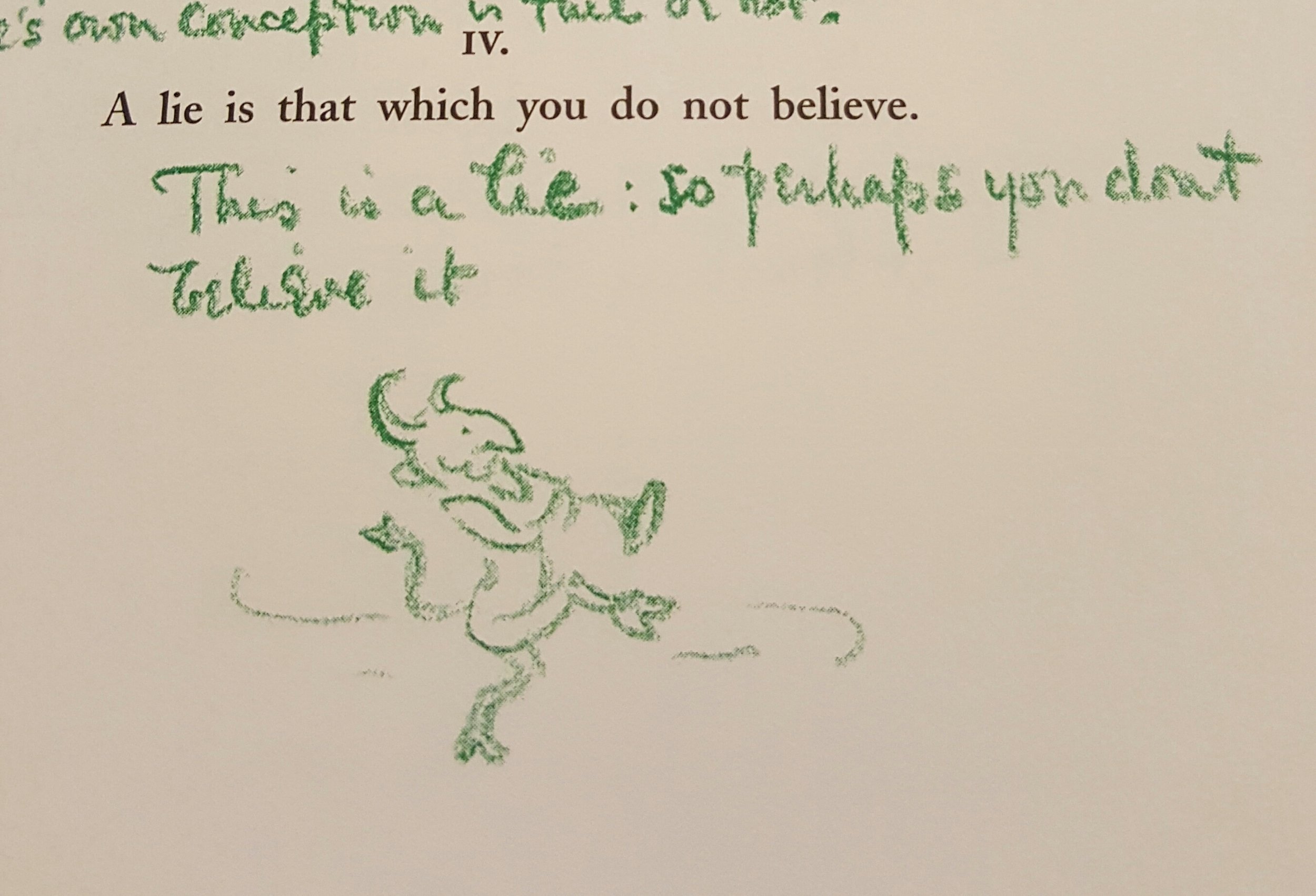

Jackson’s platitude: “A lie is that which you do not believe.”

Chesterton’s handwritten comment: “This is a lie: so perhaps you don’t believe it”

Jackson’s platitude: “Friendship is the only respectable form of human intimacy.”

Chesterton’s handwritten comment: “Puritan!”

Jackson’s platitude: “A man is a ship: his religion a harbour. Few men sail the high seas.”

Chesterton’s handwritten comment: “No, men do, except to find a harbour somewhere.”

Chesterton’s comments in Platitudes Undone refute Jackson’s maxims on life, but do so in a clever and playful way.

Like Chesterton, we live in an age at odds with the Christian vision of life. In such a setting, it is important that Christians cultivate the life of the mind. As Ken Myers says,

If ever there is a time when mindless Christianity is likely to produce menacing consequences, it is when the surrounding culture is embracing new conventions of thought, new institutional arrangements, new formative practices in the shape of everyday life.

Classical Christian educators would do well to cultivate the life of the mind and at the same time foster a creative, gracious, humble, and even playful spirit – a Chestertonian spirit! After all, in an age all too often marked by inflated, antagonistic discourse, the world could use more Chestertons, and fewer Mr. Pricklepantses.